I had a bit of a comments discussion with one of the Potwell Inn regulars yesterday, concerning what she called ‘covid fatigue’, and then someone else joined in – in the way that these spontaneous conversations pop up – you know, cold wet day outside (at least for us, ‘though not in her part of the US) and we chewed over the awfulness of it all for a bit and agreed that constant bad news and bad politics is sapping our energy. We were, all three, leaning in a virtually socially distanced way, on the imaginary bar, lamenting jobs not done and feeling a bit lethargic.

And later as I wandered around the flat, picking things up and putting them down again and sharing the umpteenth cup of green tea with Madame, I noticed – or rather paid proper attention to the fact that we’ve got one heated and one unheated propagator going, with basil, coriander, winter hardy lettuce and parsley all germinated, and the overwintering broad bean seed (Aquadulce Claudia) had just arrived in the post and we’d managed to clear most of the allotment for the winter crops. As often happens, it seems, our lethargy had been rather upstaged by our seasonal autopilot. I wrote a couple of days ago about linear versus cyclical time, and there’s no doubt that for farmers, allotmenteers and gardeners it’s a no-contest. The rhythms of the annual cycle of sowing, tending, harvesting and clearing get embedded in our minds and sink, like chi energy into our fingers.

So it was off to the computer for me, and I spent most of the daylight hours watching the rain running down the windows, and renewing the growing plan for the coming season. By the magic of the software, a single click can transfer last year’s plan to 2021 and (provided you’ve put the dates in properly) clear the beds in another click and declare that the game is on once again. Of course virtual allotmenteering is a good deal less physical than the real thing, but at least you get a big red warning when your rotations go awry – which warnings you’re free to ignore because allotments on 250 square metres are not so easy to rotate as a 400 acre farm.

The next challenge was to match our physical seed store with the virtual one, and that’s always a bit of an eye opener. If I could make a helpful suggestion to new allotmenteers it would be to steer clear of garden centre seed displays. This is advice we never take ourselves, of course, so the result of this disobedience is the annual search for out of date seeds. Yes, the second most important bit of information on the seed packet is the bit we most frequently cut off and discard – the ‘sow by’ date. Seeds, like gardeners, only stay viable for a time. If you only wanted to grow poppies you could probably bulk buy as a teenager and carry on sowing them until they cart you off; but there are other more sensitive seeds that are only viable for a year, some that need a rest in the fridge before they’ll germinate and some that won’t germinate unless they’re resting in daylight.

If I could make a helpful suggestion to new allotmenteers it would be to steer clear of garden centre seed displays.

I used to work on a radio station in which, posted in huge letters over the desk, was the legend “In the event of equipment failure RTFM”. I asked someone what it meant and he answered(testily) ‘read the manual!’. Seed packets seduce with their photos but disappoint if you don’t read the small print. Every single word.

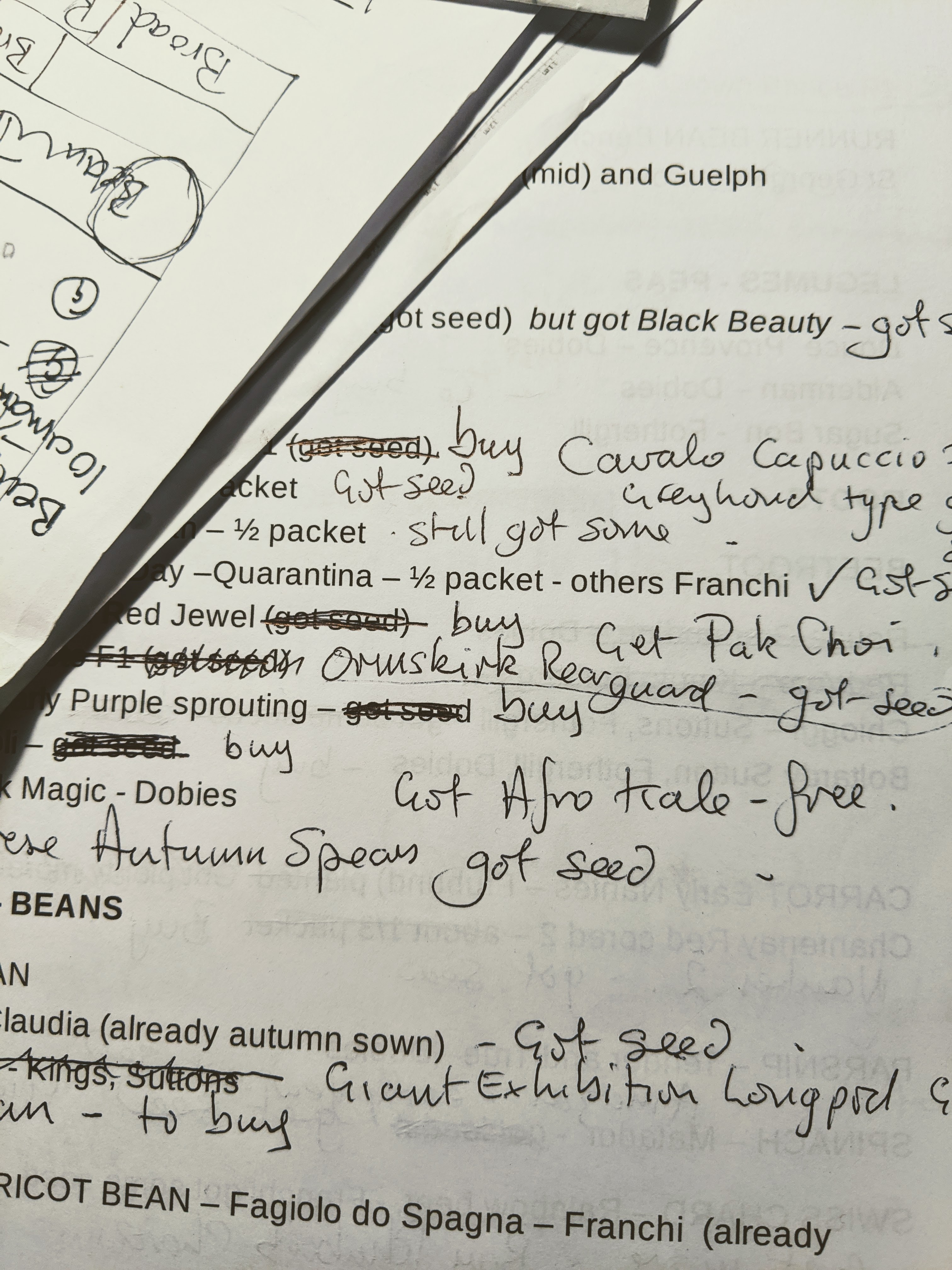

All of which failure to take our own advice leads every autumn to the clear out of un-viable seed, and we’re ruthless because you can lose a whole crop if you miss the optimum sowing time. So any packet with a missing date goes out regardless of whether it’s got seeds in it. There’s a picture (top right) of yesterday’s haul above, and if you were to examine the contents you’d discover that 80% of them were garden centre impulse buys.

Next comes the seed order; so last year’s order is reprinted as a starter, and then we go through it to remove some things we didn’t like and add some that might do better. Then we check the box(es) of seeds against what we want to grow and eventually – after a lot of argy bargy and a sheaf of notes – I get to type out the definitive seed order for – in this case – 2021, along with suppliers etc. We shall, as ever, almost certainly ignore the list as soon as we leave the virtual world and set foot on the dirt!

But it all filled a rainy day and we spent a few hours together around the table enjoying the prospect of the Promised Land in all its unrealised potential. The allotment will never look better than it does in October, inside our heads, and suddenly we realised as we sat down later that we’d crossed the Rubicon, notwithstanding covid fatigue and all the provocations. We’d strayed over the border into 20121 without intending to and it felt very good.

This morning the sun is shining as Storm Alex slowly passes, leaving floods and damage everywhere but our refurbished water stores brimming. Last season (dare I say that now?) was a huge challenge, undertaken in the most difficult circumstances. We couldn’t get new seed so we had to busk it. We couldn’t buy most of the sundries we rely on and at times we felt terribly isolated from our friends and family. Our government seemed incapable of seriously addressing the challenges and even today we have no idea how this will all turn out, but that’s all linear time. The fact is, in spite of everything we grew food, adapted, changed our whole diet to fit our circumstances and stayed better friends than ever! Nil carborundum we say, and carpe diem too, but we usually say it in some form of English as we exercise the inheritance of resilience and resourcefulness. that our parents and grandparents passed on, along with the time to plant potatoes. It’s OK to be human too.